Woodstock Aqueduct Company

By Kathy English

November 2021

While sitting in stopped traffic due to a broken water main in front of the Woodstock Recreation Center last spring, it occurred to me that I knew nothing about the Woodstock Aqueduct Company, other than their blue tank on Cox District Road… The history of the Woodstock Aqueduct Company is the subject of this paper.

First, a short history of water in Woodstock. In 1790, Charles Marsh bought a farm at the foot of Mt. Tom and built his first farmhouse. “Upon moving into the house Marsh … had water brought to his house by means of pump-logs from a spring on the north side of the hill. This was the first aqueduct laid anywhere in the region. Marsh also brought water to his farm from the Pogue” (Henry Swan Dana’s History of Woodstock).

Another early Woodstock resident, Eliakim Spooner, was described in his 1820 obituary as a man “possessed of an original turn of mind, and it is understood that the Aqueduct so much in use sixty years ago along this neighborhood and elsewhere, composed of logs perforated with an auger, was an invention of his” (Dana History). It is possible that the log aqueduct was built in about 1796 to serve a hotel on the corner of Central and Elm streets (now Dr. Coburn’s Tonic) that Spooner managed.

The hotel at the corner of Elm and Central Streets that was managed by Eliakim Spooner.

Sanatoga Springs on Dunham Hill

Sanderson Spring, on Dunham Hill, was discovered around 1830 and soon gained a considerable reputation among townspeople as a reliable and curative water source. In 1891, an enterprising man, Walter Dearborn, bought the property on Dunham Hill and began advertising the spring’s healing properties. He surrounded the spring house with a 15-acre park, pavilions, rustic bridges, and bridle paths. Woodstock became a fine summer resort, and more visitors began to arrive than the hotels in the Village could accommodate. The townspeople and the usual leading citizens realized that even an enlarged Eagle Hotel could not keep up with the demand for accommodations. Understanding the huge appeal of a medicinal spring, they raised $120,000 [about $3,600,000 in 2021 dollars] through stock in the Woodstock Hotel Company and built the Woodstock Inn in 1892 (Dana History). Today the Sanatoga Spring, as Dearborn renamed it, is on private property; remnants of the park and spring can still be found in the landscape.

Fire was a common threat throughout the country, and in 1867 destroyed all of the Village buildings between the present Vermont Standard office and the post office. This loss was no doubt on Woodstock citizens’ minds, as well as fires in Chicago and Peshtigo, Wisconsin, on the same night in 1871. The Peshtigo fire killed an estimated 1,200 people and is still the deadliest in U.S. history.

Road dust was also a Village problem, and in 1873, “[t]hirty or forty of our citizens…have conspired to keep the dust laid, in the center of the Village at least. They procured a sprinkling apparatus, a horse drawn wagon with large wooden barrel and hose, which will extend its benign influence on Central Street, from the foot of the park to the vicinity of the stone shop, and down Elm Street for some indefinite distance. Those who wish to go farther, can have their wishes gratified by paying a small sum. The sprinkling is not a permanent affaire, but is to be tried for a week, and if the results are satisfactory it will be made so. The first sprinkling took place yesterday afternoon, and would have been very successful and pleasant affaire if, unfortunately the pipe hadn’t broke first thing. It will be tried again today, however” (Vermont Standard, June 19, 1873).

“At this time Frederick Billings had been supplying water to Elm Street and Pleasant Street, but decided he would no longer do so, prompting Woodstock to look for other sources of water. In January 1879, a committee comprised of O.P. Chandler, Justin F. MacKenzie and Charles Chapman was formed to inquire as to the feasibility of obtaining a supply of water from Blake Hill, or other hills of the vicinity. Here the business ended for the present, as it was deemed inexpedient for the village to assume such an undertaking at that time” (Dana History).

Seven years later, in 1886, “[w]ith the destruction by fire of several towns about the country, Woodstock turned attention afresh to the helpless condition of a good part of our Village. The Woodstock Aqueduct Co. was chartered by the State with capitol stock of $36,000 in shares of $50 each [about $1,000,000 and $1,500 in 2021 dollars, respectively]. The general public was invited to buy stock that was issued to Frank S. MacKenzie. The Village was authorized to contract with the corporation for suppling the Village with water for fire purposes, for watering the streets and other uses for ten years” (Dana History).

“Subscriptions for the greater part of the stock having been obtained, a contract was entered into with R.D. Wood & Co. of Philadelphia, for the construction of the work. J. Randall was the Design Engineer, and T. William Harris the Constructing Engineer. The contract called for two hydrants in West Woodstock and twenty-eight hydrants in the Village that would put a hydrant within 500 feet of every house. A big hydrant was to be placed in the square” (Dana History).

In early June 1887, reservoir construction began 2-1/2 miles up Cox District Road, on Thomas Brook, at an elevation 260 feet above the Town Hall. The Williams Brook added to the supply, with a four-inch connecting pipe to the Thomas Brook. The original reservoir is located immediately upstream from the blue water tank on Cox District Road. The dam was constructed with a packed-earth embankment about 90 feet wide at the bottom and eight feet at the top, with a stone and cement core. Today you can walk out on the top of the original dam and see the Thomas Brook flowing freely to the Ottauquechee River.

The construction company brought in 75–100 Italian laborers from Boston and built a 14- by 28-foot building to house 48 men. “When it was stated in early summer that the contractors on our water works were to bring here a large number of Italian laborers many fears of disturbance and unnamable ills were created in the minds of our people. But the result has proved very different. The men have behaved like gentlemen and have attended strictly to work. From beginning to end not a single lapse from the best deportment has been reported. Our people appreciate this and have shown it by feasting the laborers with doughnuts and coffee with their dinners while they were digging the trenches through the streets.” The men employed embraced many nationalities, Italians, Germans, Swedes, French, Americans and Greeks. Within two months these hardy men had nearly completed the dam. It is possible that local women were contracted to provide food and lodging for the workers.

“In July there was a tremendous downpour, the pipes could not carry off the water and fifty yards of the partially constructed dam toppled over. It was estimated that the damage was about $100 [about $2,900 in 2021 dollars]. The break was repaired and the work progressed rapidly” (Vermont Standard, August 25, 1887).

An accident aboard the ship on which the pipe was shipped, from Florence, Pennsylvania, resulted in a serious delay, and the pipe did not arrive until September 15.

“The Mains included 13,310 feet of eight inch cast iron pipe, extending from the reservoir to the center of the village. 2,012 feet of 6” cast iron pipe, and 14,350 feet of 4” cast iron pipe from the Williams Brook for a total of seven miles of pipe. Pipes were laid 6 feet underground, and gates are so placed to shut off water of any street if so desired. There are 28 hydrants in the village, and two in West Woodstock. The water Works people are pushing things this fine weather. They have reached the center of the village with pipe laying and the streets are torn up in all directions. The pipe is placed on saw horses, the joints packed with lead and then lowered to the bed of streams and trenches. The supervising committee included Frank S. MacKenzie, Luther O. Greene and Frederick W. Wilder” (Vermont Standard).

“In late October workers closed the reservoir gates and water slowly rose behind the dam. Within two weeks the reservoir was full and water was released into the mains. Only two pipes sprang leaks. To demonstrate the pressure in the system, the fire department attached a 1 inch diameter hose to the hydrant located near the Congregational Church and shot a powerful stream of water over its high steeple. When the air is all out of the system and full pressure is on, a better showing than this will be made, though this was satisfactory. The water gauge in the Vermont National Bank, showing the elevation of the reservoir and the pressure on the water pipes is an object of a good deal of interest” (Vermont Standard). In October 1887, the Village voted at its annual meeting to pay the Company $840 (about $24,000 in 2021 dollars) per year for five years for Village use of the water (Vermont Standard, November 11, 1887). “Phenomenal weather for the time of year, and seems to have been provided purposely to allow the Woodstock Water Works to be completed” (Vermont Standard).

Water started flowing into homes and businesses in late November 1887. “The water is pure, clear palatable and soft enough for all household purposes. It being used for cooking and drinking by all who have it, and to say that they are delighted with it feebly expresses the satisfaction manifested” (Vermont Standard). Frederick Billings carried the main on to his grounds and set hydrants for the protection of his buildings. The new aqueduct was completed in December 1887, for about $35,000 ($1,000,000 in 2021 dollars).

According to its first annual report, on November 30, 1888, the Company made $1,584.07 (about $46,000 in 2021 dollars). “There are now in force 122 services, rental from which and from the village in 1889 will amount to $2,024 (about $60,000 in 2021 dollars). The Company directors were: Frederick Billings, F.N. Billings, Justin F. Mackenzie, F.S. Mackenzie, W.E. Johnson, L.O. Greene, F.W. Wilder.”

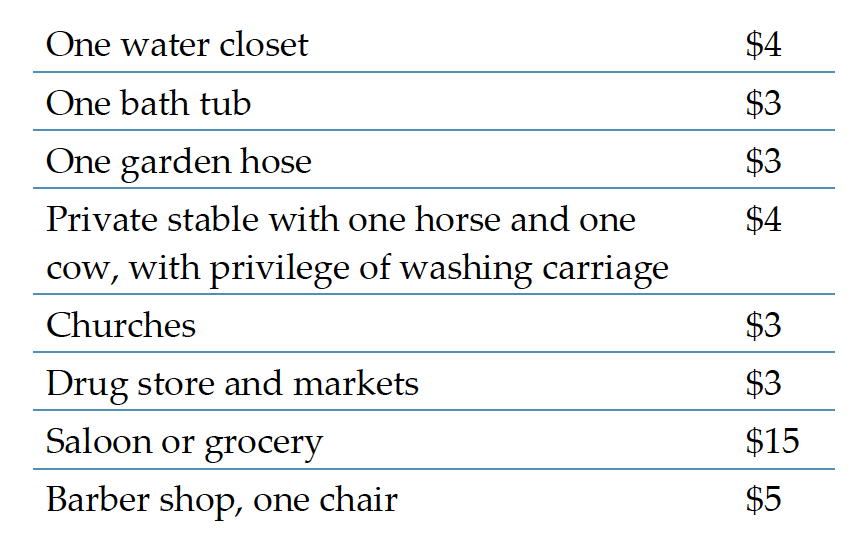

Following are a few of the semi-annual payment rates established on September 22, 1887:

“The Standard is this week for the first time printed by water power, the water being supplied by the Woodstock Aqueduct Company and our machine the Chicago Motor. It works to perfection and to say that it is a comfortable thing ‘to have in the house’ but faintly expresses our satisfaction. No fuel, no fire, no heat, no smoke, no dust, no care – really a wonderful little servant, always ready and always reliable” (Vermont Standard). Frederick Billings also bought a Chicago motor to automate the butter churn in the farmhouse basement creamery, using water piped from the Pogue. You can see it in operation today.

“One lad thought he would open the stop and waste cock in the cellar the other evening, the inside connections not being completed, to see if the water would really run. Well, he found out to his satisfaction. Before he could get help and shut the water off he was drenched from head to foot and the cellar was none the better for the flood. It will not do to fool with the water pipes when the pressure is on” (Vermont Standard, November 17, 1887).

“The laborers upon the water works have mostly left town. They have been quiet and peaceable lot of men, and have been treated well by the citizens. Some five or six of them who have been at work all summer digging our mains have concluded to remain through the winter, and have set up housekeeping for themselves on River Street, nearly opposite the gas house behind the UU Church, and propose to spend the winter there, hoping to find work in the spring. They are quiet and orderly and attend strictly to their affairs. So far as housekeeping is concerned they are destitute, and two or three straw ticks and a few blankets and comforters will save them from suffering” (Vermont Standard, November 27, 1887).

“For over a year people celebrated the fact that they had clear water flowing into their homes. On January 17, 1889, the village trustees were advised to replace the hand pump in the middle of the village square with something worthy of this achievement. They were instructed at the annual meeting to put a drinking fountain into the Square, and to procure a fountain of approved pattern, with low as well as high basins, so as to accommodate small animals as well as horses and oxen. Such a one with dippers for the humankind is greatly needed” (Vermont Standard).

In September 1889, the aqueduct pipe was connected to the new fountain; the Woodstock Gas Light Company lit the lamps at the top. Located at the intersection of Central and Elm streets, the fountain was presented to the town by Justin Mackenzie, a Woodstock Aqueduct Company director and prominent citizen who made his fortune operating mills in Quechee. Thirsty livestock drank running water from large basins, people drank from several spigots in the mid-section, and Woodstock’s dogs and cats drank from small basins placed low. Author Harry Ambrose, in The Horse’s Mouth, a book on Woodstock’s early ski history, said the grand old Victorian, cast-iron watering trough was so black, ugly and forbidding “that when I was very young I was afraid of it, and would cross the square further up by Gillingham’s.” At about the time the Woodstock Railway died, in 1933, the tar and gravel road in the downtown square was replaced with concrete paving, and the watering trough was removed. Occasionally, pieces of the fountain resurface, and one of the basins was used as a watering trough for the animals in Pearson’s Wild Animal Farm. Water still flows to the island dummy and streetlight and is used by garden club members who tend the summer flowers at the base of a lamp post and elsewhere in town.

The MacKenzie fountain, in the Village Square. (Photo from woodstockhistorycenter.org)

In 1896, the Company had 311 customers, each one responsible for the line between the main and their house or building. Now that the Village had a lot more water running through it, the question of a sewer system arose, and sometime in the 1890s the Village constructed one. A map, dated 1899, shows the sewer lines paralleling the aqueduct mains. Untreated wastewater flowed into the Ottauquechee River until the late 1950s; the pipes are still visible, if you know where to look.

In 1903, the Company bought land across Cox District Road from the original reservoir that included the Vondell farm of 86 acres and the Gillingham lot of 33 acres.

Frozen water pipes were a perennial problem at the turn of the twentieth century. In 1905, “[a] frozen water pipe on Pleasant Street was finally thawed out last week, this work, which was in charge of Wilbur Smith, Superintendent of the Woodstock Electric Company, being the first of the kind ever done here. Several men were digging three or four days to get at the pipe and picked and chiseled their way through nearly seven feet of frozen earth as hard as rock. Last year, in the same place, barrels of hot water we’re used to clear the pipe, but this year some experimental electrical work was resorted to. A wire was strung from a pole near McKenzie’s barn to the pipe and another to the cut-off in Tribou park, about 200 feet away. A transformer reduced the current to 104 volts and this was applied to the pipe, which was warmed up and cleared in about an hour after the right connection had been made. With special apparatus, the work could be done in a much quicker time, Supt. Smith says. At West Woodstock, Tuesday electricity thawed out a pipe in twenty minutes, one wire being attached to the sill cock at W.C. Vaughan’s house and the other to a hydrant in the street. The pipe was frozen somewhere between the house and the road, but electricity found and started the water without any digging or other trouble” (Spirit of the Age, February 18, 1905).

“Electrical Apparatus” to thaw pipes can be bought on the Internet today.

In 1908, there was a major drought across the country, and in Woodstock the Company was able to draw water from the Pogue for a few weeks, for fire suppression. The next year, the Carleton Hill reservoir was built, at a final cost of $37,880.61 (about $1,130,000 in 2021 dollars). Unfortunately, within 20 years the concrete failed, and in 1929 the Company started discussing developing a reservoir in the Vondell valley.

In the 1920s, water users reported muddy water in the system, and in 1923, the Company purchased and planted 5,000 trees around the Cox Reservoir to improve water quality. Meters to measure usage were installed in 1928. The first reference in the Company minutes to shutting off water was to the White Cupboard Inn, for a bad debt in 1930.

In 1943, a chlorination building was built at the Cox Reservoir, but the water did not taste good. My husband, Charlie, recalls being sent for water with his wagon and jugs to the Dreer Spring on Golf Avenue, and to another private spring on Mountain Avenue, up the shared driveway between the look-alike houses, that was available to residents of Mountain Avenue and River Street with permission.

“By the early 1950s the company realized it needed more water and tried to buy The Pogue from the Billings family but were unsuccessful. It might have been a blessing as the water quality was not good, and they would have had to build a water filtration system at an enormous price” (Vermont Standard).

In 1953, the Cox Reservoir was dredged and enlarged. The dredging spoils were placed around the Pogue to raise its level. Today, these fortified banks are used as a lovely, level walking path.

There was a severe water shortage in 1954. In 1955, the Company finally confronted the muddy water problem and declared a 40% rate increase to pay for a new filtration system to remove sand and silt at the Cox Reservoir. The system was completed in November 1956 and cost $28,000 (about $280,000 in 2021 dollars).

In 1961 and ’62, the Company again looked for new water sources and developed the Vondell Reservoir, located at the end of the Aqueduct Trail that starts on Cox District Road, opposite the enlarged reservoir. By 1963, the completed Vondell Reservoir added 28 million gallons of surface water to the system.

In the early 1970s, the Company stopped using surface water stored in reservoirs and began to pump water from a deep well on Route 12, at the Bassett farm. Today, water is drawn from a large, ancient aquifer. If you stand near the Company solar panels and look around, you will see a huge circular drainage system coming off Route 12 from The Ledges and the walls of the surrounding bowl, created about 13,000 years ago when the ice-age glacier covering the area melted. The area is often underwater in the spring, a recent problem for the Pomfret school. It takes about five years for this surface water to percolate to the top of the aquifer, and all Village residents depend on it for their drinking water supply. Energy collected by solar panels, installed in 2015, powers a pump housed in the small building nearby. Here the water is chlorinated and pumped along Route 12 directly into the Village system. Citizens use about 350,000 gallons a day.

Blue holding tank on the Cox District Road.

In 1989, the large blue holding tank was built just below the original reservoir on Cox District Road; it holds about one million gallons and acts as a water tower that pressurizes the system. The Cox and Vondell reservoirs became backup water for emergencies.

Across Route 4 from the White Cottage, there is a chain link enclosure that houses the water terminus from the holding tank on Cox District Road. During Tropical Storm Irene, Village residents were required to boil their water, due to flooding at this site. Should flooding re-occur, the Company has built a backup main from the Cox District Road tank, which crosses the Ottauquechee River at the high school playing field and connects to mains located on higher ground.

Maintaining any water system is an ongoing effort. Interestingly, many of the original 1886 cast-iron mains still function, due to mineral deposits from the hard well water that coat and seal the inside of the pipes. Most problems occur on Elm Street. When necessary, local excavators are on call; Gurney Brothers Construction did the large excavation at the Recreation Center last year. And while parts of the system are antique, it is run with modern tools: Nathan Billings recently installed a sophisticated computer program to monitor and control pressure at various points in the system in real time, and identify breaks in the mains. At night, when usage is low, water is added to the tank on Cox District Road to maintain the system’s pressure.

Today the Company has 42 stockholders, most of whom are descendants of the original stockholders; the Billings family owns 52% of the stock. The current Board Directors are Jireh, Frank, and Nathan Billings, Tom Debevoise, Eric Wegner, and Jay and Steve Morgan. The Company complies with the same rules and regulations that govern all municipal water utilities in Vermont; this includes a yearly report to customers of water test results.

Acknowledgements

Many, many thanks to Matt Powers, Executive Director of the Woodstock History Center, for his research and enthusiasm for the Company, which included a two-hour driving tour of all aqueduct sights, with his commentary. Special thanks to Jireh Billings, who has a complete set of Company minutes and plans to someday write the Company’s definitive history.