The Tradition of Basketmaking and Basket Use in Woodstock and Beyond

By Matthew Powers

The Black Ash Tree and the Making of a Basket

The single most important basketmaking tree of the Northeast has always been the black ash (Fraximus nigra), also known as Hoop, Basket, Brown, or Swamp Ash. It is a small to medium-sized tree usually attaining a height of 40 to 60 feet with a trunk diameter of 1 to 2 feet. The moisture-loving black ash is a lowland tree that grows throughout the northeastern United States and southern Canada in swamps and bottomlands, as well as the rich alluvial soil areas found near and along rivers, lakes, and streams. Northeastern basketmakers have always known how to locate, and keep secret, the rare stands of black ash using their experience to decide which trees would provide the best material for their craft. A young tree, a hand’s breadth in diameter, was usually selected due to its straight trunk that was generally free of scars, knots, and other blemishes.

A basketmaker cut a suitable tree into short sections or billets, removed sections of their bark, and pounded them with a mallet or the butt of an ax until the growth rings separated from each other to form long strips that ran along the grain of the wood. This tendency to separate is unique to ash trees. After separating the growth rings, a basket maker trimmed and split the strips into thin ribbons. These ribbons are quite flexible and not easily broken. “Once a basket maker started a split, he or she could pull the strands apart by holding one side in each hand and applying slow and steady outward pressure or by pulling apart the splint against the sides of a wooden vise held between the legs. The inner faces of the resulting ribbons of ash were smooth and silky and required no further finishing, but the craftspeople had to scrape smooth the rough and grainy outside edge with a knife. Generally, the satiny inside face of the splint formed the outside of the basket.” Each maker created basket forms that served dozens of different purposes, providing containers for gathering, processing, measuring, and storing food and other materials. Unlike wooden containers, baskets had the great advantage of being lightweight. The basket weaves and embellishments can also be unique to each maker or cultural tradition.

Local Tradition

The Harlow Family

An important familiy in our area to contribute to the tradition of basketmaking is the Harlow family. There is documented evidence that at least three generations of Harlow family members worked as basket makers. The first Harlow family member to be listed as a basket maker was Leonard Harlow (b. 1788 in Windsor, VT). It is likely that Leonard’s father, William, also carried on the trade but, unfortunately, census records and other resources documenting members of the family prior to Leonard do not list people’s occupations.

Leonard and his wife Sarah lived in Barnard until after 1815 when they moved to Northfield, Vermont, where they lived until about 1833. They returned to the Barnard area and then settled in the adjoining town of Pomfret where they farmed and Leonard ran a basket shop with his sons. Leonard and Sarah later moved to Randolph, Vermont, where Leonard died in 1858. He was still listed as a basket maker in the 1850 census. Sarah returned to Pomfret where she lived with her sons Augustus and Benjamin. Augustus and Benjamin carried on the business at their basket factory on the Stage Road in Barnard, close to the Pomfret town line. Augustus was said to have been the business man of this basket making family. Augustus died in 1881 ending the partnership between the brothers. Benjamin continued to work as a basket maker into the early 1900s, eventually moving to West Windsor. Augustus’ daughter, Harriet, married a man named Joseph La Mountain in 1878. He must have learned the trade from Harriet’s father and uncle as Joseph is listed in the 1883/1884 City Directory as a manufacturer of baskets in a shop in South Pomfret. Perhaps he took over the business after Augustus’ death until the sale of the family farm in 1896. Joseph did not carry on the basket making tradition long term as later in his life he became the superintendent of the Woodstock Aqueduct Company.

In 1908, the Harlow basket factory was disassembled and moved by sled during the winter to its present location in the South Pomfret village area. Land was purchased by the Teago Grange, and the building was reconstructed to become a branch of the State Grange of Vermont. The Harlow basket factory/Teago Grange building was renovated in 2017 to become the Grange Theater at Artistree for theater arts.

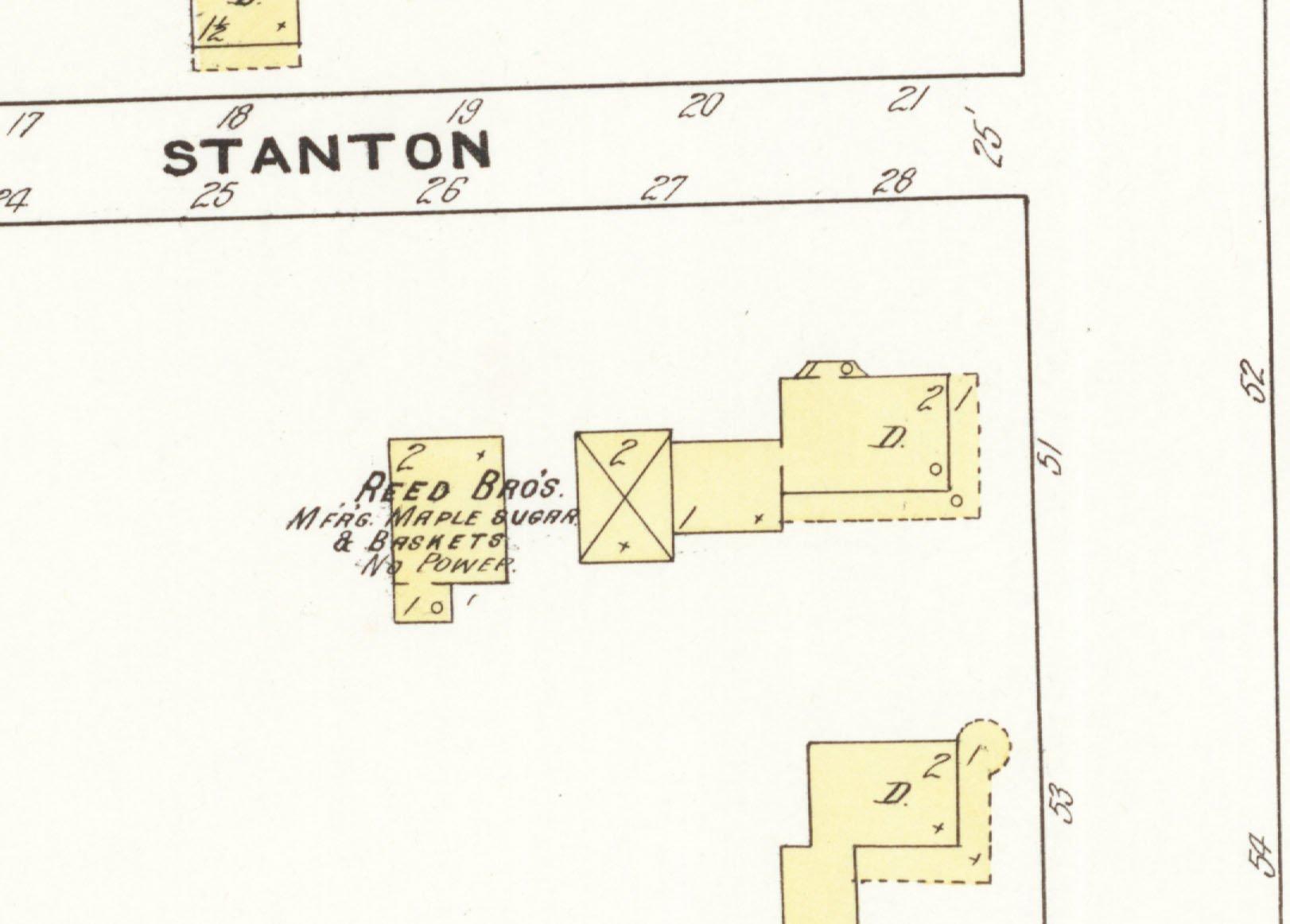

Although the Harlow basket factory and farm had been sold, Benjamin’s son, George, continued to carry on the basket making tradition. He worked for the Reed Brothers who had a maple sugar and basket making business in the Village of Woodstock.

Harlow houses in Pomfret. Possible location of the Harlow basket factory. 1856 Hosea Doten map of Pomfret.

The Harlow basket factory.

This building was originally used as the Harlow basket factory before being moved in 1908 to South Pomfret village. It is now The Grange Theatre for ArtisTree.

1916 City Directory. Woodstock, Vermont

Benjamin Harlow. Circa 1860s.

Possible Benjamin Harlow tools. Handle maker, splint maker, basket form. Collection of the Old Mill Museum. Weston, Vermont

Joseph La Mountain in his later years.

The Reed Family

Henry B. Reed (1831-1894) was a major producer of maple sugar and controlled at one time three sugar houses and six evaporators. In 1882, he hung 3,500 sap buckets on his land and other rented land. Somewhere along the line he also learned the basket making trade at the Harlow basket factory. Henry taught his sons how to make baskets as well as helping with the maple sugar business when they lived on a farm on Happy Valley Road in Taftsville. They worked together from some years and then Henry’s sons established themselves on Pleasant Street.

Henry’s sons, Fred and William, brought their maple sugar and basket making business to Woodstock village in 1889. The business, Reed Brothers, was located in a building at the rear of William’s house. “In a little room at one end of the lower floor is the sugar-making equipment, but most of the space is given up to the basket business, and here the ash logs are pounded and torn into strips for weaving.” The business seems to have merged with the Harlow family basket tradition as it is stated in The Elm Tree Monthly in 1916 that, “From this department comes the thump or ‘ping’ of hammers, that can be heard in the street whichever way the wind blows. Ten to one, George Harlow is doing the pounding, for George, who is the son of Benjamin, and therefore is of good basket making blood, has been pounding ash logs for forty years. ‘I’ve pounded a lot of ‘em,’ he remarked between thumps.”

The Reed Brothers basket business produced approximately 3600 baskets of varying sizes in a year. They also had a stock of fancy baskets on display (“small, shallow, round or oblong, in various shapes, and sometimes having a bit of color”) that were made by George Harlow. The Reed Brothers retired in 1926, and they both moved away from Woodstock to live with family. The business was purchased by the Deerfield Farmer’s Exchange in Wilmington, Vermont.

Reed Brother’s house and maple sugar and basket making business. Sanborn Map. 1910. The shop sign at the Reed’s house on Pleasant Street said, “Maple Sugar and Baskets.”

Work Basket. Attributed to the Harlow/Reed Family. WHC collection.

Sturdy double-handled workbaskets were essential for harvesting apples, potatoes, and other fruits and vegetables as well as for storing them in a root cellar. Although there are no identifying marks, it is likely that this basket was either made by the Harlow family or at Reed Brothers.

Utilitarian baskets

The Harlow and Reed families most likely made many of the utilitarian baskets seen in Woodstock area photographs as well as the objects in the collection of the Woodstock History Center. It is a testament to their craftsmanship and heritage that these baskets continue to exist.

Dr. White and his field baskets.

A sturdy oak handle provided the strength needed to haul heavy loads of apples, potatoes, and other crops.

Field Basket

Woodstock and other surrounding town farmers used deep round baskets like the one in this photograph to harvest potatoes, corn, and other heavy crops.

Large wool basket. WHC collection.

Large cheese basket. WHC collection.

The Richardson Legacy

Clyde Richardson (1904-1983) had a life-long interest in wood working and learned the hand basket making trade as a boy from George Harlow. One might suppose that Clyde could be found hanging around the Reed Brothers’ basket shop. He carried on the tradition as a hobby for many years, and he eventually inherited tools used by the Harlow and Reed families after George’s death in 1928. He held onto these tools at least until 1955 when he made a “permanent” loan of them to the Vermont Guide of Old-time Crafts and Industries in Weston, Vermont. It has yet to be determined if the Guild still retains the tools.

“Indian” Baskets

Prior to the nineteenth century, the New England Indians in the Woodstock area most likely created baskets to coincide with their seminomadic life that was closely linked to the seasons, seasonal events, and weather cycles. Native life was drastically altered and disrupted with the influx and imperialism of European populations over the course of several centuries. The decimation of Native populations due to disease and war, as well as the displacement and disenfranchisement of Native people, contributed to the increased dependency on trade with their white neighbors. Basket making became one of the main crafts that could be sold or bartered with whites. There were many years of peddling their wares from door to door, offering baskets that were popular for store, farm, and household use.

While the basket trade was an important economic resource to Native people, New England and New York Indians continued to make baskets for their own use throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. “The earliest New England Indian splint baskets were square or rectangle, and because many were used for storage, lids were a common feature. Artisans decorated early baskets with brightly colored abstract or geometric designs, which they stamped or painted in place after weaving the basket. Natural vegetable dyes such as indigo (Indigofera sp.), walnut hulls, or the red berries of Solomon’s seal (Polyganatum sp.), or commercial dry pigments mixed with water and animal-hide glue were often used to color the splint.” “They often wove dyed and undyed splint together to create horizontal bands or patterns of color; they also combined colored splint with stamped or painted designs to produce vividly decorated surfaces.”

Woodsplint basket with lid.

Artist once known. Native American. Ash and pigments. Collection of the Woodstock History Center.

Detail of storage basket and lid.

The interior of the storage basket and lid is lined with newspaper most likely to protect personal possessions. The newspaper on the lid is glued with an 1818 newspaper while a later newspaper lining in the main basket structure is threaded around the top.

A simple abstract design was painted on the four sides of this basket.

The Tourist Trade

When the tourist industry began to take hold in New England, Indigenous people began to cater to populations that liked fancy baskets with embellishments that included sweetgrass, porcupine weaves, and a variety of dyes. “Basketmakers usually wove fancy baskets over carved wooden molds, which allowed them to achieve a tighter weave and to replicate the same basket form again and again. Artisans could craft small or odd shapes much more easily over a mold as well. Most makers of fancy baskets cut their splint with a gauge, a simple tool made by setting a row of metal teeth into a short handle. Using a gauge, a basketmaker could cut a strip of prepared splint into several narrow lengths of precisely the same width. Molds and gauges greatly facilitated commercial production work and helped ensure uniform quality from basket to basket.”

There were likely Native people who were selling baskets at boarding houses and other establishments in Woodstock. The fancy baskets shown in this article represent Native craft as designed for commerce. While we do not know their place of manufacture, we can assume that many of these baskets were used in Vermont. “Some baskets were probably made in Vermont, while others were probably sold here by basket sellers from New York, Canada and Maine. Others were probably purchased by Vermonters or given to them as gifts.”

Artist once known. Open Work Basket. WHC Collection

“The best fancy baskets strike a balance between traditional Indian techniques and color combinations and the wonderful excess of Victorian design.”

Artist once known. Covered work basket. WHC collection

Covered work baskets were almost always round with a tight cover. They were made of ash splint standards with braided, twisted or straight sweetgrass weavers. This basket has a small braided sweetgrass handle on the top.

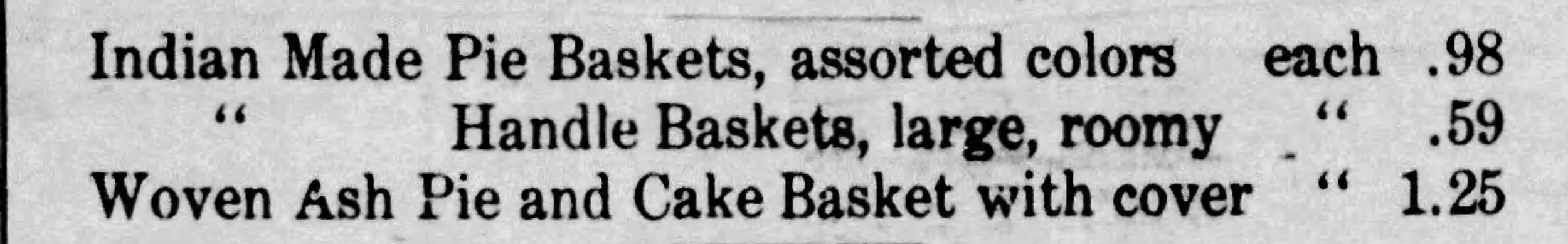

The were several Woodstock stores such as J.B. Jones, E.A. Spear, and F.H. Gillingham’s that were advertising Indian made baskets for sale in the early 1900s.

A Complete Line of Souvenirs

Baskets made by the St. Regis Indians at E.A. Spear’s store. The Vermont Standard. August 17, 1905. “In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Indians in many areas of the Northeast formed basketmaking cooperatives. In addition to making baskets for direct sale to the tourist market, some of the cooperatives sold to white middlemen, who in turn marketed the baskets through regional department stores and mail-order catalogues.”

Indian baskets at F.H. Gillingham’s. December 21, 1933.

Passamaquoddy Pie Basket

This example of an “Indian made” pie basket from Maine might be similar to those being sold at F.H. Gillingham’s in Woodstock in the 1930s.

Artist once known. Arm Basket. Private collection

One of the most common Indian basket forms found in Vermont are these thin but wide baskets, usually with sweetgrass weavers. Many of these are found still containing vintage sewing materials. “We can envision women traveling to a neighbor’s on a cold winter evening with an arm basket firmly under the arm; ready for a sewing bee.”

Interior of arm basket.

The vibrant hues of indigo dyed splints were meant to capture the attention of buyers.

“Demand for northeastern Indian baskets fell drastically during the Depression. Fewer people could afford to take vacations and buy souvenirs, and tastes also changed dramatically, moving away from the fussy old-fashioned quaintness of the late Victorian era and toward the spare industrial designs and man-made materials of the Art Deco era. Traditional handcrafts fell out of fashion. After World War II, the introduction of inexpensive plastic containers combined with a flood of cheap imported baskets to doom the northeastern Indian basketmaking industry.”

Environmental Crisis

Currently, the biggest threat to the ash tree and its use as a heritage craft is the Emerald ash borer (EAB), which is an invasive species that was discovered in southeastern Michigan in 2002, probably arriving on solid wood packing material from Asia. The beetle’s larvae feed on the inner bark of ash trees, disrupting the tree's ability to transport water and nutrients which ultimately kills a tree. As of 2018, the EAB is found in 35 states and the Canadian provinces of Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Manitoba.

If you suspect Emerald Ash Borer, contact the USDA at 1-866-322-4512. For more information visit: www.emeraldashborer.info

Although millions of ash trees have been destroyed over the last twenty years, steps are still being taken to protect this type of tree with treatments and “biocontrols.” Seed saving, breeding programs, and replanting efforts will hopefully help this species to survive.

Education, awareness and action are the key to this tree’s survival. At the heart of the effort is preserving yet again another important tree species in its natural habitat and to preserve the heritage of basket making. Educational efforts continue to disseminate information in English and Native languages about baskets in collections, basket making techniques, and how to work against the demise of the ash tree.

“We have an obligation to that tree to do everything in our power to help it survive—for itself, our culture and our baskets.” Black ash “is a metaphor for being Native.” she says. “It is Indigenous. It is how we survived: being flexible, without breaking.” Jennifer Neptune.

Emerald Ash Borer, Adult - David Cappaert

Article Resources

Shaw, Robert. American Baskets. The Cultural History of a Traditional Domestic Art. Clarkson Potter Publishers. New York. 2000.

“A Silent Killer: Black Ash Basket Makers are Battling a Voracious Beetle to Keep Their Heritage Alive.” Anne Bolen. American Indian Magazine. Spring 2020, Vol. 21 No. 1

Late Period (1890-1970). Indian Baskets in Vermont: Part 1. Frederick M. Wiseman. Indigenous Vermont Series, 2012:9. The Wobanakik Heritage Center, Swanton, Vermont

“Good Baskets, They are made in Woodstock.” The Elm Tree Monthly and Spirit of the Age. December 1916.

EAB’s Destruction of Black Ash Threatens a Native American Tradition: http://www.emeraldashborer.info/view.php?id=24