Quicksand in Woodstock

By Jennie Shurtleff

When I was in kindergarten, my brother - who was three years older than I - came home from school telling how a pair of oxen had vanished long ago in the quicksand that was around the Pogue on Mount Tom. At the time, I was both horrified and intrigued. My only experience with quicksand was vicarious as I had seen on television where someone - usually the show’s villain - would inevitably fall into a pit of quicksand, which would effectively result in his/her demise. Upon hearing about the quicksand on Mount Tom, I wanted to go see it, and I was somewhat disappointed after the long hike up to the top of the mountain that none was to be found.

A 19th-century view of the Pogue before it was enlarged.

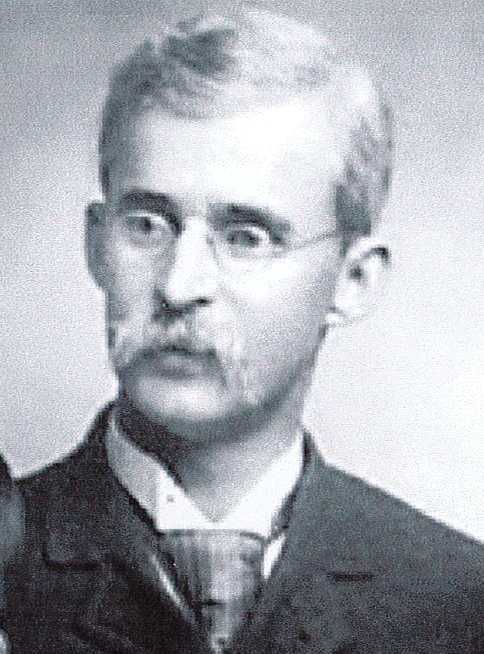

Above: Professor Edward Williams, Jr.

Moreover, after many, many (I am old) decades of searching, I’ve never located any quicksand – at least none that would provide a Hollywood-style ending for a villain. On the other hand, over the years I have noticed that there are many buildings, roads, and other structures whose foundations have moved or shifted, and if Professor Edward Williams, Jr. is correct, “quicksand” might be part of the reason.

Professor Edward Williams, Jr. was a part-time resident of Woodstock in the early 20th century, as well as one of the founders of the Geological Society of America. He wrote several articles in the months following the Great Flood of 1927 that ravaged Vermont on November 3rd and 4th of that year. In one of these articles, published in the Vermont Standard on November 24, 1927, Professor Williams explains that his early knowledge of Woodstock’s geology came in the 1850s, when his grandfather - none other than the redoubtable Norman Williams of library fame - drove young Edward all around the town and told him about the land, its composition, and the method of building roads in the town’s early years. According to Edward, his grandfather knew a bit about the these topics as he had assisted in building a number of the roads both in Woodstock and the adjoining towns.

In his article, Professor Williams then goes on to note that “Woodstock is crossed by the deeply filled valley of the Ottauquechee River, and the depth of the filling is shown by the breadth of the ‘flats’ on which the villages of the town are built. The filling is of glacial material, and in all that was deposited in quiet water is quicksand – from the slight proportion in the sands we use for road material, through the gravels to the deposits in the lake bottoms of clean quicksand which looks like clay when dry, but bogs our roads when wet, and forms the mud which, when dry again, drops off our boots. This universal portion of quicksand makes all of our soil easily moved by rains, and when water is high, scours out banks and bottoms of streams.” In this article, Professor Williams suggests “that no effort to make permanent repairs [after the Great Flood of 1927] be made until the actual condition under ground is fully understood.”

Several months later, in the December 1, 1927, edition of the Vermont Standard, Professor Williams writes another longer article that provides more context for the issues caused by the area’s geology.

The area that he focuses on is outlined in red on the map. In his article, Williams begins by describing what was found after the debris from the Great Flood of 1927 was cleared away, and he then explains how these findings support anecdotal historical evidence that this area in the center of what is now the Village of Woodstock was swampy and why it was likely called a “spruce hurricane” by the first white settlers to the area.

Williams states, “The original surface of this area, after the flooded conditions were cleared away, was more or less clean and open gravel, underlaid sporadically by absolutely clean quicksand free from inclusions. The gravels were water-soaked, as the village area, for want of a better name, was called ‘a Spruce Hurricane’ across which our streams ran with shallow depth and retarded flow. Our immigrant fathers saw spruce endeavoring, in vain, to send roots into underlying quicksand and stand upright when high winds blew and easily pushed them flat.”

“Into this tangle the streams brought a supply of bush and vine material that grew freely and made river-flow difficult. Rough channels were cleared for both streams, and a dam was placed across the Quechee. There is little scour above a dam, and there were no very high waters then, but it does not take much power to move gravel, and the Quechee floor below the dam began to lower and the cutting was north of the houses built on North Park street. Later the dam just south of the jail bridge was built, to fill such scour as had obtained along its bottom. Thus as the Branch bottom rose, so the Quechee bottom lowered, and there was a free outlet into the latter of such water as soaked into the open gravels underlying the above about the Park. In fact, the water supply in the above-named area was from shallow wells or pipes driven into the gravels.”

“Freshets in the Branch filled the gravels to heights that seepage could not drain, and the cellars of the stores and houses in the area were filled to a definite level. The store cellars were pumped dry; those under the houses were drained into wells sunk into the gravels in the middle of the main cellar, and thus these times of abnormal high water went to clear better ways through the gravels, and springs developed along the south bank of the Quechee – that back of the Hatch house had the largest and most persistent flow. But our freshets were never abnormally high, and no cracks developed; no sinking occurred, and no tendency to walk into the river was observed. In fine, the depth of the bottom of the Quechee below that of the Branch was inconsequential….

But times were changed, climates were changed, flood controls destroyed, and the gentle showers of our immigrants exchanged for torrential and long-continued downpourings. High water came into both streams. The gravels carried larger supplies from the branch to the River with great speeds and along a steeper channel. The rising floods prevented an easy delivery, and the gravels became filled with seepage water which could not be delivered. Matters might have gone on without hurting the bridge or the adjacent houses; but the long embankment north of the bridge became a dam with insufficient outlet between the abutments, the water piled up abnormally, and with head sufficient to dig a five-foot hole into its bottom north of the bridge, as always occurs at constrictions, no matter whether the bottom be loose gravel or solid stone. In addition the head induced by this rise sent water southward into the gravels beneath these North Park street houses. As long as the flood remained, the head kept the water from flowing back. No cracks came at once. The first one was slight and the flood still high. With water approaching an ordinary flood came settlement; with low water came cutting along tops of quicksands, and into the river came bank and trees.

The Tudor House shown on the right side of the above photo used to stand at 21 The Green. The foundation of this house was compromised by the Great Flood of 1927, and the house had to be torn down in the years following the flood.

The bridges must be made safe at once. As for the houses: will the town remove the solid approach from the north and put in an arched concrete approach on strong concrete piers, so that the future high waters can spread harmlessly over the broad and low gardens? If so, it may be well to consider remaining and making expensive repairs: if not, it will be less expensive to build elsewhere, as this flood is by no means the last, if present conditions continue.”

If Professor Williams is correct, many of the problems today that plague some of the structures along the Ottauquechee’s southern bank have likely been exacerbated by the building of dams in the 18th and 19th centuries and the presence of “quicksand” that was deposited in ancient times. Although Williams does not cite his fellow Woodstocker George Perkins Marsh (the author of Man and Nature, or Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action), it is clear that Williams and Marsh shared many of the same beliefs. Moreover, since both had lived in Woodstock, they had a front row seat to the negative impacts that human beings had on the environment and the necessity for change.