By Jennie Shurtleff

Before the widespread availability of dental care, toothpaste, toothbrushes, and chemical compounds like fluoride, dental problems were ubiquitous. In recent years, numerous research studies have linked oral health to overall well being. However, even without the benefit of systematic studies, as one reads about those who suffered from dental issues long ago, one can see the impact that their dental problems had on other facets of their lives.

The diary of Charles M. Cobb, a young boy living in the mid 1800s in one of the less affluent sections of West Woodstock, sheds light on the pervasiveness of dental issues.

In one diary entry Charles talks about his aunt, Sarah Cobb, whose teeth had "ulcified" and she had to have them pulled. Sarah died at the young age of 33. No cause is listed for her death, and it is possible that there were multiple contributing factors; however, one can assume that ulcified teeth made it difficult for her to eat a healthy diet, which in turn could have compromised her health.

Closer to home is Charles’ mother, Lucia, whom Charles describes in one diary entry as having “one side of her face swelled on account of her teeth.” Lucia did not go to the dentist, but rather Charles says that at 8 P.M. he “went up to Hiram's & got some spirits of turpentine to put on [her teeth]” as she clearly was in pain. In addition to her tooth problems, she suffered from general health issues and often felt ill.

As for Charles himself, his teeth were a constant source of not only physical pain, but also emotional turmoil. In his diary on March 19th he notes: “I find one personal defect about me that is worse than any of the old ones. My teeth are rotting - already several have got holes in the enamel, and this very day I've had quite a touch of tooth-ache the first real perfect toothache I ever had, tho' I felt a little something some days ago. It's a new and beautiful sensation. Were I a person of importance I would of course go down to Dr. Chase and get those holes filled up. But alas! I'm scarcely worth what 'twould cost. Mother never had a tooth fixed for the same reason. But I swear, if my teeth ache hard I'll have 'em filled before I ever lay out a cent for any other purpose. Whether I can obtain a cent for 6 months or not.”

The next day on March 20, he states: “I'm poor as a scarecrow, my breath stinks, and my teeth unless I rub 'em all the time are overlaid with tartar.” Two months later, on May 12, he comments: “Just at night Father mended Alden Thomas's boots & got 15 c. - Alden was at work for McClay. He has since been at work for Henry, and is going to work for him this week, so I shan't get any money that way, to get 2 teeth filled & buy me some breeches. More soon.”

Three days later, on May 15, Charles states: “My teeth will all rot out, first I know. If I had a little cash, I would get 2 or 3 teeth filled & get me a decent pair of everyday pantaloons.” The following day, May 16, he notes, “I'm neither so healthy, stout, or good looking. My teeth are rotting too, cuss it. But complaining will do no good.” A week or so later, on May 24, he adds, “About my teeth I do know certain. They'll ache nice sometime before long. Well in 1848 I was pretty plaguey fair looking specimen of a boy & was calculating to do great things. - What I am now. - Well, - if I can keep comfortable till I get ready to give up the ghost, I shall do well.” While Charles doesn’t directly state the connection between his sore teeth, his general health, and his belief that he could be successful, the positioning of his sentences suggest that he felt the three were related.

A week later, on June 1, Charles, still concerned about his teeth, states, “Coming home I got some gum, & took a wax impression of a hole in one of my teeth, that I can't see. It was larger than I supposed.”

Over the next three months, Charles does not dwell on his teeth. However, it is clear from his diary entries that he was working hard and saving his money. True to the promise that he had made to himself earlier in the year — to get his teeth fixed if he could earn enough money — in his October 20 diary entry he notes that: “Had a cold-toothache yesterday. Have had teeth filled to the amount of 3.75 since Sept 12. by Mr. J.N. Haskell, late of Bethel -- 32 teeth in my head yet.”

Tooth and oral problems not only plagued the working class, but also those of the middle and upper classes. Case in point, young Edward Dana, commonly called Ned, grew up in the Dana House that is located at 26 Elm Street (the building that houses the present-day museum for the Woodstock History Center).

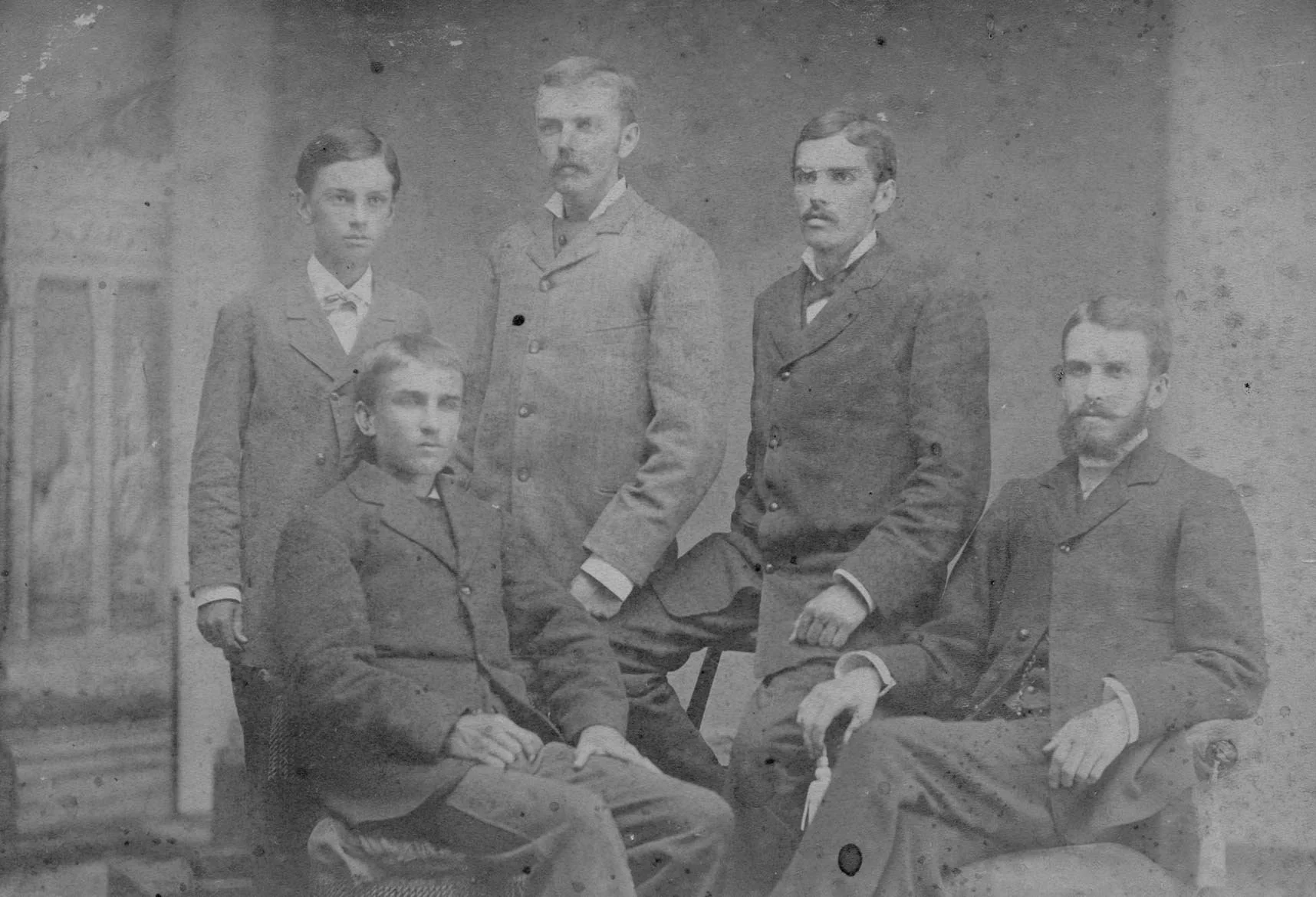

Edward Dana, sitting front left, is shown with his four brothers.

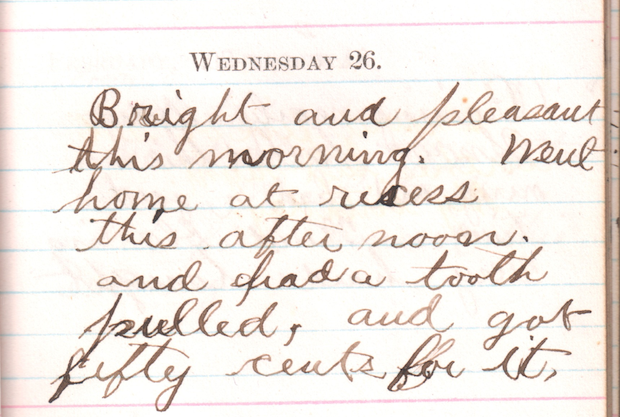

Ned lived a privileged life that allowed him to have good clothes and often attend parties and other forms of entertainment. Despite his privileged lifestyle, however, as a young teenager in the 1870s, he kept a diary in which he mentioned having tooth aches. Unlike young Charles, however, who waited for months until he was able to earn enough money to have his teeth fixed, two weeks after Ned mentions he had a tooth ache, he records in his diary that he had the tooth pulled, and he was given 50 cents for having to suffer through the ordeal.

Ned’s diary entry after having his tooth pulled.

Based on portraits, it appears that Edward was not the only Dana to suffer from dental problems. The portrait of his grandmother, Mary Dana (above left), shows an older woman whose mouth appears sunken, likely suggesting tooth loss.

Certainly late portraits of George Washington suggest that he, too, suffered from dental issues. At the time of his death, he had lost all of his natural teeth. This is likely because of taking calomel – or Mercurous chloride – which was used to treat a variety of health issues ranging from yellow fever to constipation, but had numerous negative side affects such as causing teeth to loosen.

Portrait of Mary Gay Swan © Woodstock History Center

Gilbert Stuart, Portrait of George Washington. Image courtesy Clark Art Institute. clarkart.edu

Dental care during the 18th and 19th centuries was clearly far from optimal, and even many treatments during the 20th century seem archaic to us now. While many Americans are fortunate to have appropriate dental care, many others — both in the United States and throughout the world — still suffer from the same type of pain that was a pervasive and integral part of life for our forbears.